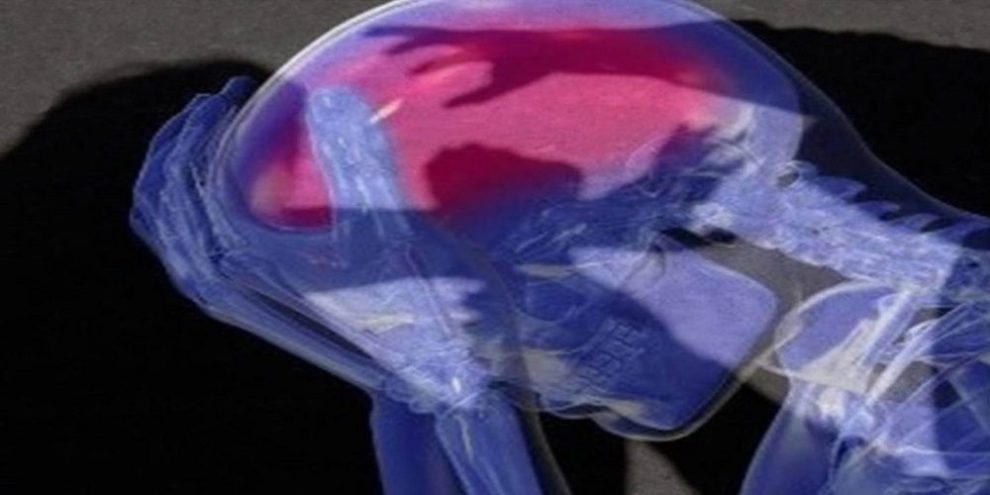

In the hunt for why criminals engage in criminal behavior and especially why some show such violence and aggression within their crimes, the prevalence of traumatic brain injury has not gone unnoticed. In fact, in a number of studies carried out with prison inmates, the rate of head injury has been seen up to seven to eight times higher than the rates found in the general population.

A new research study from Australian researchers was published in July 2015 in the research journal PLOS One, which aimed to investigate a possible link between traumatic brain injury and criminal behavior. By studying the hospital records of almost 8000 patients alongside their first-time criminal convictions, an idea of how they may be related has emerged.

There have been many notorious cases of criminals whose earlier brain trauma has come to light and in some cases, put forward as a possible explanation for their callous and brutal violence against others.

Fredrick West, a serial killer in the United Kingdom, who along with his wife Rosemary West was responsible for the deaths of ten women and girls at their home at 10 Cromwell Street in Gloucester, experienced a motorbike accident when he was 17 years old. This left him in a coma for a week with serious head injuries which required a metal plate to be surgically inserted into his brain to try and repair the damage.

Peter Sutcliffe, the ‘Yorkshire Ripper’, another infamous British serial killer, was a premature baby and starved of oxygen at birth, potentially damaging the hippocampus in his brain which is involved in regulating aggression.

Investigating Brain Injury and Criminality

This study in Australia used record linkage where a large dataset gained from records is used to make a comparison and analysis against another variable. In this case, on whether there are any correlations between traumatic brain injury and first criminal convictions.

Previous studies have been carried out using a similar methodology. Notably, a study looking at brain injury in childhood and the risk of criminal convictions in later life within Northern Finland, was published in 2002 in the journal Psychiatric Research. Here they found there was an increased risk of over one and a half times for criminality if an individual had suffered a traumatic brain injury as a child.

Another study that looked at the risk of violent crime in people with epilepsy and traumatic brain injury in Sweden, published in 2001 in PLOS Medicine (Fazel et al, 2011) found a three-fold increased risk of convictions for a violent offense compared to the general population after a traumatic brain injury which required hospitalization.

These results do suggest there is a casual link between the two and therefore if traumatic brain injury can be reduced, it is possible this could have a positive impact on crime reduction. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) can range from a knock to the head causing blackout and concussion to more severe trauma which requires medical intervention.

A milder head injury is more common and does not result in any lasting effects on cognition or behavior. Another issue to be considered is there are behaviors that can be seen in the early years of childhood which have been linked through research to criminal behavior in adulthood, and these behaviors are also linked to a higher risk of head injury.

The interrelationships between mental health, substance misuse, and criminal behavior particularly violence and aggression are complex, and it can be difficult to disentangle these factors and consider causation.

A Longitudinal Retrospective Cohort Study

In this study, individuals born in Western Australia between 1980 and 1985 who had a traumatic brain injury that required hospital treatment were identified from hospital records. For every individual found which matched these criteria, three people of the same age and gender, also born in Western Australia, who had never had a traumatic brain injury that required hospital treatment were selected.

These were to act as control subjects to provide a baseline comparison for the targeted subjects of the study. This research also identified all the full genetic siblings of the same gender of targeted brain injury subjects who were born within 5 years of their year of birth (either earlier or later). These were siblings who did not have any history of brain injury but as they grew up in the same environment as the targeted individual, they would have experienced very similar home life, upbringing, and social exposure. If there was more than one sibling available, the one that was closer in age to the targeted subject was selected.

Hospital records were also used to ascertain whether any mental health problems were present or had been treated. Any history of substance abuse was examined using records from the Western Australian Drug and Alcohol Office.

Using the Western Australian Department of Corrective Service’s records, researchers were interested in criminal convictions, especially the first criminal convictions of any of their research subjects. Their records search included juvenile crimes up to the year 2009 and adult offending up to the year 2011, along with community-based orders and custodial sentences as the outcomes from the Court system. A separate analysis was completed for cases of violent offenses covering homicide, assault, or robbery.

Any subjects who had a criminal conviction before their brain injury were excluded from the study. Researchers wanted to focus on individuals who had no criminal history before their brain injury but did have a criminal conviction after their injury, to see if the injury itself was involved in behavior changes that may have led to this conviction. They also only looked at individuals whose criminal conviction was at least 12 months after their brain injury to allow for any resulting behavioral effects to occur.

A notable downfall in these measures is participants would only show on these hospital-based measures if they have received treatment for an episode of mental illness or substance misuse that had come to the attention of the authorities.

In many instances, an individual can be suffering from mental illness without experiencing a hospital admission or similarly, enduring substance misuse without coming into contact with relevant agencies and organizations with regard to treatment and support. While this method would have picked up on severe cases, many may be missed using this record check alone.

The control subjects who had a criminal conviction but no actual brain injury were given a pseudo-traumatic brain injury date, matching the target subjects in terms of age and gender. This was to try and ensure the population control subjects could be as closely matched to the test subjects as possible in order to make any findings more valid and more directly comparable to the population in general.

An analysis was completed through statistical modeling with univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression models. This allows for all data and potential other factors to be entered into the models and included in the analysis. Regression analysis is designed to search for correlations between variables, for example as one variable increases, does the other increase with it, decrease, or stay the same?

After exclusions were made due to convictions before brain injury and convictions taking place too early after brain injury:

- A total of 7694 people were included in the analysis

- 5018 males and 2676 females

- The average age when brain injury occurred was 10.5 years for males and 7 years for females

Traumatic Brain Injury Vs General Population

Compared to community population controls, those who had experienced a traumatic brain injury had twice the level of conviction records. In males, 18% of brain-injured subjects had conviction records compared to 10% of the population controls. In females, 9% of brain-injured subjects had conviction records compared to 4% of the population controls.

When compared as a whole to community controls, results indicated that traumatic brain injury increased the risk of any criminal convictions in both the male and female target groups.

Interestingly, when looking at the same-sex full siblings of the brain injury subjects, there was an increased risk of offending for the brain injury males but not for the females. For both males and females, there was an increased risk of offending for all of the associated factors looked at including mental health record, drug, and alcohol record, and social disadvantage.

Overall the results of this study support an increased risk of offending, including violent offending, when an individual has suffered a traumatic brain injury that required hospital treatment. Furthermore, these results support previous studies which have also found a significant correlation.

At best this study can be taken as further evidence that there is a casual link between traumatic brain injury and criminal behavior, but cannot go as far as say that traumatic injury is a cause of criminal behavior. There are clear relationships between the effects of a brain injury and how that can impact behavior. For example, a person recovering from a brain injury can experience changes in their personality, thought patterns, and their cognition ability as the physical brain tries to recover.

Some of these changes can be temporary however many can be long-lasting and can have a significant impact on that individual going forward. They may find their impulsivity, emotional processing, and social behaviors have altered. These changes will manifest in their behaviors and may well lead to a higher risk of becoming involved in criminal activity which they may not have done so previously.

The authors of this study suggest that this causal link does indicate that a reduction in the prevalence of traumatic brain injury could have a beneficial impact on criminal convictions and crime rates in the long term.

It is clear that further research into this area would be necessary to try to narrow down this relationship and provide more actionable results which could be taken forward, especially with regard to the complex interrelationship between social status, mental health, substance misuse, and criminality.

- Bennett, W. (1995) The Horrific Secrets of 25 Cromwell Street. The Independent. Published 7 October 1995.

- Dusetzina SB, Tyree S, Meyer AM, et al. Linking Data for Health Services Research: A Framework and Instructional Guide [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2014 Sep. 4, An Overview of Record Linkage Methods.

- Fazel, S., Lichtenstein, P., Grann, M., and Langstron, N. (2011) Risk of Violent Crime in Individuals with Epilepsy and Traumatic Brain Injury: A 35-Year Swedish Population Study. PLOS Medicine. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001150

- Harmon, K. (2012) Brain Injury Rate 7 Times Greater among U.S. Prisoners. Scientific American. Published 4 February 2012

- Schofield, P.W et al. (2015) Does Traumatic Brain Injury Lead to Criminality? A Whole-Population Retrospective Cohort Study Using Linked Data. PLOS One. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132558

- Timonen, M et al. (2002) The Association of Preceding Traumatic Brain Injury with Mental Disorders, Alcoholism and Criminality: the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort Study. Psychiatry Research. Volume 113, Issue 3, pp217-226

Guy, F. (2017, Jan 09). Research Study: The Relationship Between Traumatic Brain Injury and Criminal Behaviour. Crime Traveller. Retrieved from https://www.crimetraveller.org/2017/01/traumatic-brain-injury-criminal-behaviour/

Prefer Audiobooks? Audible 30-Day Free Trial with free audiobooks

Shared this. If brain damage is the reason behind someone committing a horrible crime, does that mean they can’t be held fully responsible? A head injury isn’t their fault. I am not sure though whether changes to personality or behaviour because of a head injury is enough to override their own personal choice in carrying out a crime.

I find this very fascinating. I love looking at the psychology of the criminal mind, and I’ve never thought that a traumatic brain injury could be part of the reason behind it.